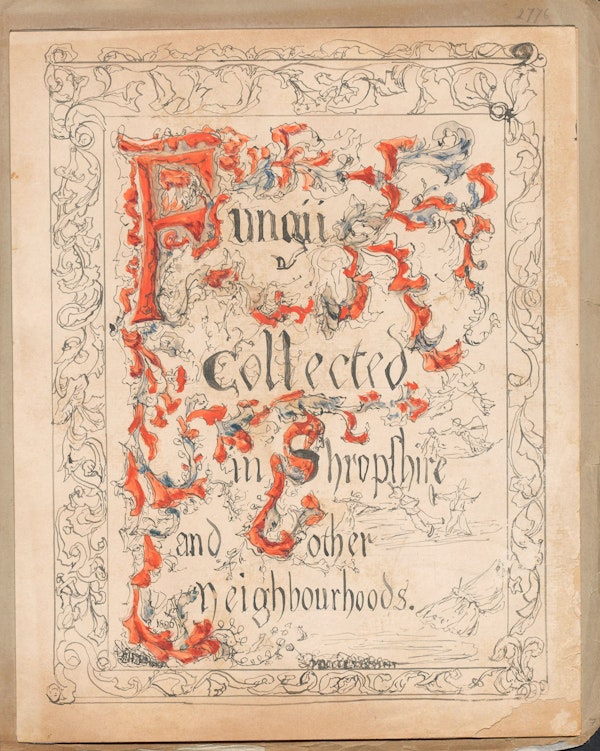

Fungi Collected in Shropshire and Other Neighbourhoods (1860–1902)

From umami-rich meals to poisonous and psychedelic specimens, mushrooms have represented something queer, sexy, and dark for centuries.

As temperatures drop and leaves fall, blanketing forest paths and city sidewalks in layers of red and orange, nature’s decomposers spring from the ground. Transforming organic matter into fertile soil, fungi and their vast underground networks work silently beneath our feet. October is peak mushroom season for many, as foragers trained in the art of finding tasty, meaty morels and hen-of-the-woods also begin their labor. Our fascination with fungi, one of the oldest organism groups on earth, has remained a human constant. From umami-rich meals to poisonous and psychedelic specimens, mushrooms have represented something queer, sexy, and dark for centuries.

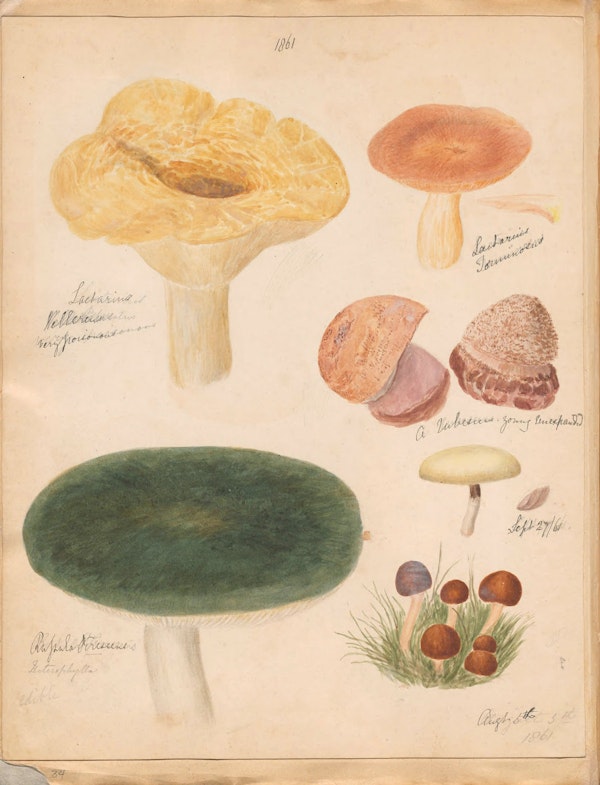

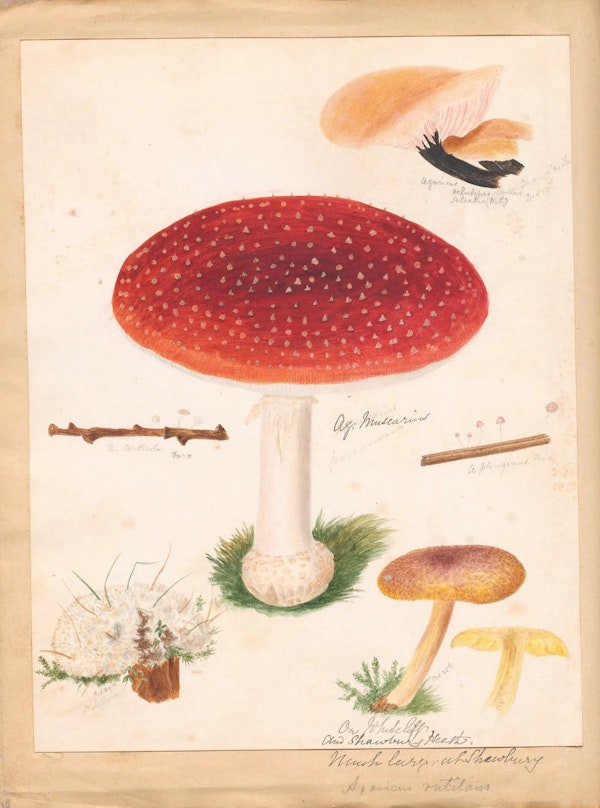

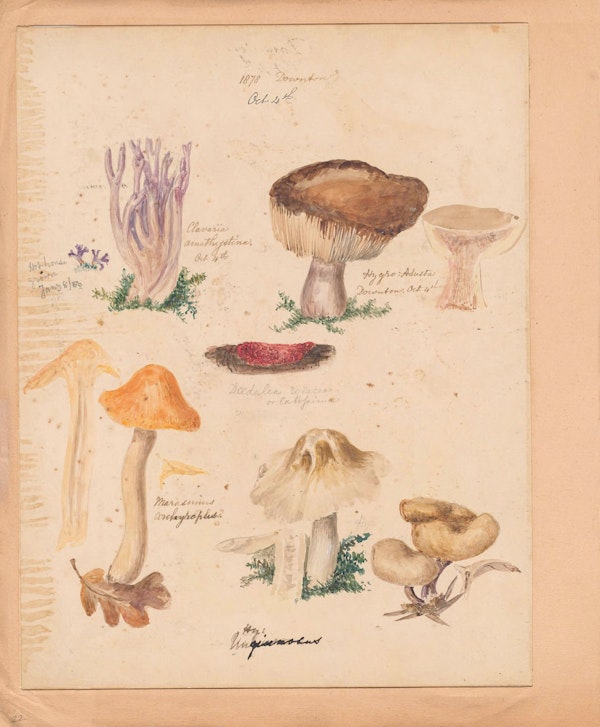

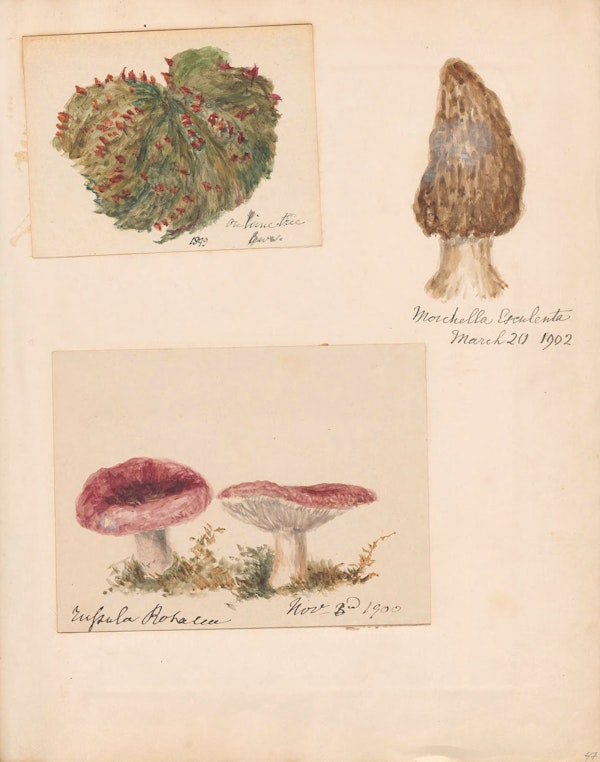

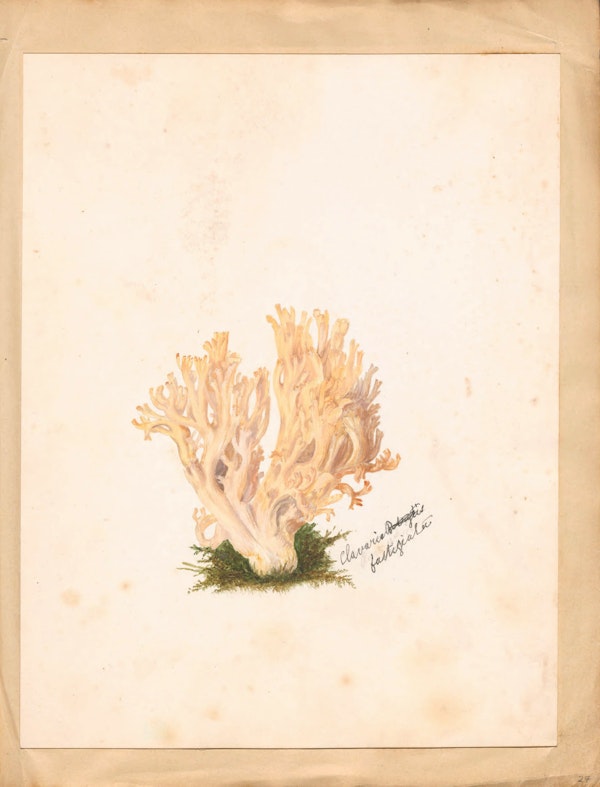

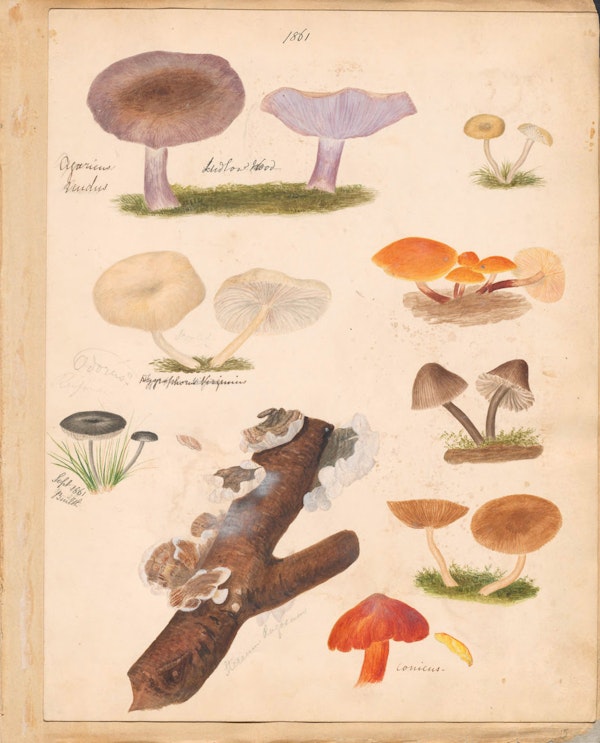

Behind recent calls for fungal futures — involving everything from “biohacked” bodies to anti-capitalist visions — lie carefully illustrated descriptions of the mushroom world by naturalists like M. F. Lewis. Bound into three exquisitely colored volumes with filigreed title pages, her Fungi of Shropshire features hundreds of species, collected across forty-two years of work in England and Wales, rendered in pencil, watercolor, and ink. Despite the enormity of Lewis’ project, little is known about her life — we have yet to discover her first name. What we do know is that she was deeply and intensely committed to studying mushrooms.

The title of these three volumes, Fungi Collected in Shropshire and Other Neighborhoods is a bit of a misnomer: her illustrations, which range from the recognizably red-and-white spotted fly agaric to smaller, drabber species, were produced over many hundreds of miles, painting a stunning portrait of Britain’s rich fungal diversity in regions seldom explored by mycologists. Most pages feature several species collaged together, sprouting from vegetable hosts or moldy organic matter. Lewis’ pages avoid the classificatory divisions of typical herbaria (or, in this case, fungaria), grouping mushrooms mostly by aesthetic arrangement rather than taxonomic relations.

Like many other women naturalists in the second half of the nineteenth century, Lewis appears to have collected and illustrated specimens for her own edification, combining her “polite” training in the arts with meticulous scientific observation against the backdrop of a growing embrace of natural history’s wonders. As some women filled their parlors with seaweeds and skeletonized flowers, Lewis turned her eyes to something decidedly darker. Scraping through rotting leaves and the animal feces from which mushrooms sprung, Lewis saw the beauty in these odd, seemingly unclassifiable specimens (we didn’t separate fungi into their own kingdom until the 1960s), emphasizing their sumptuous colors and casually ignoring their potentially poisonous qualities. Anticipating what would become a full-blown mycological fever later in the nineteenth century — most clearly demonstrated by beloved children’s book author and mycologist Beatrix Potter — Lewis knew that mushrooms were for more than consumption. They held scientific and aesthetic value amidst showier flowers and elegant ferns, even as they worked within a system of decay in which death preceded reproduction.

It’s unclear whether today’s obsession with fungi — tracked in recent books by Litt Woon Long, Merlin Sheldrake, and Anna Tsing — is another fleeting trend or a longer embrace of our primordial ancestors, bred by an increased understanding of these deceptively massive, spore-producing organisms’ importance for a networked world in peril. What is clear, though, is that the beauty and diversity of the fungal world has captivated amateur naturalists and artists for centuries. From the smallest mushroom caps to sprawling, fleshy, phallic specimens, women like Lewis chose to study fungi over other plants, animals, and everything in between, pointing to the artfulness in decomposition, the liveliness of rot.

Below you can browse highlights from the only known copy of Lewis’ work, courtesy of Cornell University Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Text by Elaine Ayers — Originally published on Public Domain Review.